“CATTLE WOULD WINTER IN THESE VALLEYS WITHOUT OTHER FOOD OR SHELTER.”

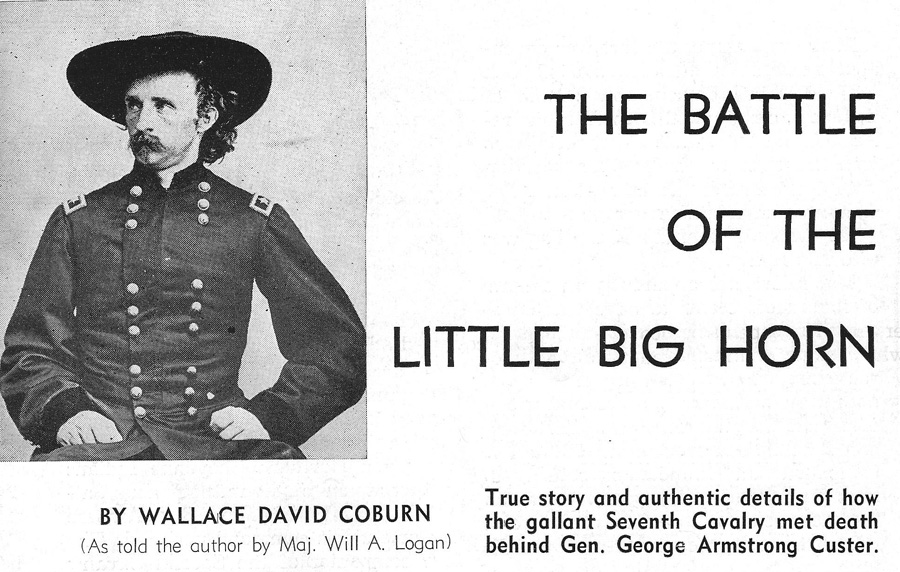

GENERAL CUSTER PROMOTED BLACK HILLS AGRICULTURE

BY JACK MCCULLOH, RAPID CITY, SOUTH DAKOTA

The map of South Dakota has over 49 place names because of one trip the US Frontier Army took through the territory. Tilford, Ludlow, Custer Peak, and Trail City in Corson County are on the map to memorialize the Army’s trip through The Great Sioux – Cheyenne reservation led by George Armstrong Custer. When the territory eventually became a state in l889 one of the first names chosen for a County seat west of the Missouri River was Custer County located in the southwest corner of the new State.

The Mormon Church had accomplished a major population shift into a new territory in the West from Missouri and Illinois. For years thousands had struggled overland for California Gold; and the Montana Gold Rush moving west along the Platte River on established roads. Those with goals of reaching the West had no interest in the Black Hills guarded by hostile Indians on their trip through “the Great American Desert.” 1

CUSTERS ORDERS TO THE TROOPS TO THE BLACK HILLS

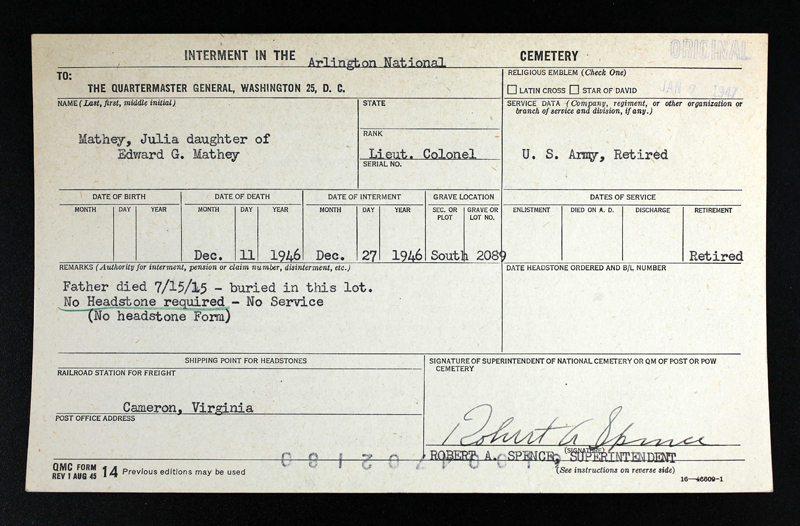

……… care will be taken not to molest or in any manner disturb any Indians who may be encountered on the march, unless the latter should first act in a hostile manner . . . This command is about to march through a country infested by Indians, more or less hostile, and even should the latter, as it is hoped, not engage in general warfare and the usual acts of hostilities, there is no doubt but that they will endeavor to make captures of stock and to massacre small parties found imprudently beyond the lines . . .” his military dispatch of July 15, 1874 from Prospect Valley, Dakota (” . . . Our march thus far has been made without molestation upon the part of the Indians . . . As I sent pacific messages to all the tribes infesting this region before the expedition moved, and expressed a desire to maintain friendly relations with them . . . [o]ur Indian guides think differently, however, and believe the Indians mean war. Should this be true they will be the party to fire the first shot . . .”); and his second military dispatch, from Harney’s Peak, August 2, 1874 (” . . . gold has been found at several places, and it is the belief of those who are giving their attention to this subject that it will be found in paying quantities. I have upon my table forty or fifty small particles of pure gold, in size averaging the size of a small pin-head, and most of it obtained to-day from one panful of earth . . . Until further examination is made regarding the richness of the deposits of gold no opinion should be formed . . .”). 2

The Black Hills of Dakota Territory are different than the nearby Black Hills around Laramie, Wyoming. The Northern Black Hills are a lot like an inverted bath tub on a flat prairie – 40 miles wide and 80 miles long with a geological rim running around the base of the Hills. These Black Hills are about the size of the present day state of Israel.

The Army explored around the Black Hills of Dakota several times before Custer’s trip. Before the Civil War the army had sent expeditions around the Black Hills including Harney in 1855, Warren/Hayden in 1857, and Raynolds in 1859. These military expeditions did some mapping but none had entered the Black Hills before Custer. In 1868 the US War Department sat down with the Great Plains War Chiefs and in the Treaty setting up the Great Sioux – Cheyenne Reservation the Indians agreed to stop fighting people for a price. 3

Proclamation of Gen. McCook against

Occupation of the Black Hills of Dakota

I, Edwin S. McCook, Acting Governor of the Territory of Dakota, by direction of the President of the United States, do … warn all unlawful combinations of men …, that any attempts to violate our treaty with these Indians, … by an effort to invade … said reservation, will not only be illegal … but will be disapproved , and Government will use … military power … to remove all .. who go there in violation of law.4

The first time the Army actually entered the Black Hills was in 1874. Everyone at that time knew you could find gold. The only question was how much and could you get it?

The War Chiefs agreed they would hunt in certain areas for a limited time, receive annual issues of sugar, coffee and cattle, and would stop harassing the railroads and settlers. The US Government agreed to remove the manned forts they had established protecting the Bozeman Trail. It’s the only treaty with Indians the government ever entered into that removed military posts from territory to be settled by the spreading population.

CHEAPER TO FEED THAN FIGHT

In the Secretary of War’s report of 1874 he wrote; “The feeding process by 1874 has been now continued for six years with the Sioux, has so far taken the fight out of them….They have been sitting down at the agencies along the Missouri River, to risk the loss of coffee, sugar, and beef in exchange for the hardships and perils of a campaign against soldiers. As a result the Custer expedition penetrated to the very heart of their wild country, and returned without any opposition; and the military camps at Red Cloud and Spotted Tail Agencies are in safety, though surrounded by a force of fighting men from ten to twenty times larger than their own number. To have tamed this great nation down to this degree of submission by the issue of rations is in itself a demonstration of what has been so often argued – that it is cheaper to feed than to fight wild Indians. 5

The purpose of a thousand men and their supply wagons entering the Hills and finding a route was to record what was there. President Grant was near the end of his second term as President, and he spoke bluntly to the Indian Chiefs when they visited him in Washington D.C. that he expected them to live in peace on reservations. He would not allow free roaming Indians to check in just to receive food, clothing, and money. Grant’s policy was — if you choose to roam/live free off your reservation; your tribe will not receive annuities – or land grants – or cash payments. Sioux Chiefs such as Spotted Tail and Red Cloud resisted being counted in the census claiming it was against their religion. Grant put a stop to their tribes receiving anything until they were counted.

Grant would not negotiate directly with the Chiefs; instead, they must negotiate with the Secretary of the Interior and the Church run (Quakers) head of the Indian Bureau.

Grant wanted Indians treated as citizens of the United States and insisted they deal with the Government through the responsible agencies. He amended the law to make Indians citizens instead of banning them as citizens. He expected them to learn English, and make their own way in a short time by working land. Indians were issued plows, seeds, and farm equipment.

The chiefs on the Northern Plains knew that Congress had designated reservations as sovereign areas and the army could not enter reservations except by permission of the tribal councils. Some insisted as heads of “Sovereign nations” they would deal only with the President – not with Indian Agents assigned by the Government – because as heads of nations they had equal rank of the President and they did not like Indian Agents telling them anything. The chiefs wanted to select their own agents to act for the Government in providing for them.

Grant lost his patience with argument and ordered the Secretary of the Interior (Columbus Delano) at the time which was essentially a privately run church related welfare operation financed largely by Government manpower and money, to feed and cloth only those Indians living full time on reservations .He also ordered the army headed by General Sherman to remove tribes from non reservation land after a two year deadline to their reservation. Trail herds of cattle from Texas had for several years been grazing during wintertime in Montana territory, replacing the depleted Buffalo herd on the Plains , and cattlemen wanted Indians put on reservations , not free and able to steal horses , raid local ranchers and run off their cattle herds.

In the Great Plains the Sioux and Cheyenne claimed hunting areas by treaty. They argued Grant could not take away rights approved by Congress in 1869, but never signed by two thirds of the bands affected called for by the treaty. The treaty let the railroads through the Great Sioux Reservation along the Platte River. Congress let the time limited parts of the 1868 Treaty run out (food and clothing) and expected Indians to be in “Indian Territory” (present Oklahoma) – or on reservation they set up in limited states on a case by case basis.

CUSTER BOOSTS AGRICULTURE FROM HARNEY PEAK

“Twenty six days were spent traveling inside the Black Hills, and about 300 miles of valley were traveled by the command. Placer Gold was found …; The search for gold was not exhaustive, … but at one point a shaft was sunk to a depth of eight feet, and gold was found amounting to five cents per pan at the top, … to twenty cents at … eight feet. ……Custer’s Gulch, where twenty of the explorers took gold claims, declaring their intention to work the claims as soon as a possession of the country can be obtained, seven miles south of Haney’s Peak.”6

When he climbed Harney Peak Custer wrote a promotional pitch. He said

“Cattle could winter in these valleys without other food or shelter than that to be obtained from running at large.” His published report caught the attention of Gen. William B. Hazen, commander of Fort Union, at the junction of the Missouri and Yellowstone rivers, who was convinced the Great Plains was the Great American Desert.

‘”The lands are not worth a penny an acre,” said Hazen, and in the winter “men and beasts perish from cold.”

Custer thought General Hazen was fond of notoriety and “consequently scribbles a great deal for the papers.” Custer wrote a nine column article in the Minneapolis Tribune (published April 17, 1875, shortly after the Black Hills Expedition) refuting Hazen ……Custer had extravagant praise for the Black Hills country.7

“Agriculture in no portion of the United States, not excepting the famous Blue Grass region of Kentucky, have I ever seen grazing superior to that found growing wild in this hitherto unknown region. I know of no portion of our country where nature has done so much to prepare homes for husbandmen, and leave so little for the latter to do as here. In the open and timbered spaces a partly prepared farm of almost any dimension, of an acre and upward, can be found here. Not only is the land cleared and timbered for both fuel and building, conveniently located with streams of pure water flowing through its length and breadth, but nature oft times seems to have gone further, and placed beautiful shrubbery and evergreens in the most desirable locations ….The soil is that of a rich garden, and composed of a dark mould of exceedingly fine grain….Nowhere in the States have I tasted cultivated raspberries of equal flavor to those found growing wild here…Wild strawberries, wild currants, gooseberries, and wild cherries are also found in great profusion and of exceedingly pure quality. Cattle would winter in these valleys without other food or shelter than that can be obtained from running at large.”8

Joe Reynolds read these reports in the Chicago Inter Ocean newspaper while working successfully his gold claim in the mountains of Colorado. He was working a claim in high country near Leadville and decided to pack up his mule and head for the Black Hills. He settled in Custer, and returned to Colorado to bring back a wife. He developed a homestead in what today is known as Reynolds prairie. Today Ivan’s son is still operating a ranch on Reynold’s Prairie

CUSTER TAKES REPORTERS TO THE BLACK HILLS

What the first journalists in the Black Hills reported stimulated thousands moving to the Hills from all directions, filling up of the country to overflowing in 1875. Thousands of jobless, underemployed and immigrant men read in the papers the word “gold” and decided to head for the Black Hills.

New York City’s population at the time was near 2 million; Chicago was near 400,000, Kansas City was 350, 00, and Minneapolis was just short of 100,000.

Newspapers sent reporters with the Army to report on what was out their in unknown territory. The public was always interested in the activities of the hyperactive Civil War cavalry officer – George Armstrong Custer. Reporters invited along paid their own way, including horses, to be on the outing. 9

Promoting Agriculture and Grazing

“Portions of the Black Hills are well fitted for agriculture, especially those from two to three thousand feet above the level of the sea, and all are adapted to grazing. The general elevation of the hills varies from four to seven thousand feet above the level of the sea, their base alone having an altitude of from fifteen to twenty-five hundred. From this it will be seen that they are not very high, taking their altitude from base to summit.

“When the present expedition returns, mining companies will be organized to test the value of the minerals found, and they will go fully prepared to overcome all opposition from the combined force of Sioux, Arapahoes, and Cheyennes, who will soon throng the region in quest of game for their Winter food; and if they contain any treasures of importance these Argonauts will soon make the fact known.”10

The Acting Secretary of Interior Smith in his annual report of 1874 wrote;

“A military expedition to the Black Hills caused great excitement among all of the Sioux people. They regarded it as an infraction of their treaty, and were filled with the fear it might lead to their exclusion from a country they highly prized.

“The exaggerated accounts of rich mines and agricultural lands given in dispatches of Custer and news reporters with the expedition increased the eagerness of people to take possession of the country. The correction of these exaggerated claims, by statements that no indications of mineral wealth were found, and that the lands were undesirable for white settlements, along with the strict prohibition of the War Department of any intrusion into the Territory did not stop parties from fitting out and leaving from Yankton, Bismarck, Denver, and Helena Montana.”11

The dispatch of Custer announcing gold in the Black Hills set off a stampede of fortune-hunters into Lakota territory. Although the 1868 Fort Laramie Treaty requires the government to protect Lakota lands from intruders, federal authorities were asked and felt they had to protect the miners traveling along the road Custer blazed for them, which they call “Freedom’s Trail” and the Lakota call “Thieves Road.

The Army with less than 25,000 men on active duty in the entire Army failed to keep Gold seekers out of the Hills with several companies. So did the 25,000 Sioux who were not fighting among themselves and other bands scattered all over the Great Sioux Reservation.

Both the Army and the Indian Tribes failed to keep the public out of the Hills when the public got Gold Fever.

THE LAKOTA WAR – 1876

A Senate commission meeting with Red Cloud and other Lakota chiefs in 1875 to negotiate legal access for the miners rushing to the Black Hills offered to buy the region for $6 million. But the Lakota refuse to alter the terms of the 1868 Fort Laramie Treaty and declare they will protect their lands from intruders if the government will not. So Congress repealed the 1868 treaty in 1877, stopped all benefits the Indians argued they were to receive, and Congress took back 40 million acres of land.

END NOTES

(1) The Northern Pacific Railroad was built during the years of 1872-1873 to Bismarck across the River from the site of Ft Lincoln Custer was assigned to build. During those years, the country west of the 100 Meridian (which runs through the middle of South Dakota) had an above average rainfall. This resulted in a perception the land was suitable for farming. Custer reported the abundant grass on his 1873 expedition to Montana. His reports along with the railroad’s advertisements designed to sell land and entice settlers west, painted the country as conducive to settlement. Hazen refutes these claims by reports from those who experienced the normal seasons that received little rainfall.

(2) Samuel J. Barrows went with the Yellowstone Expedition of 1873 and with the Black Hills Expedition in 1874 as a reporter for New York newspapers. Barrows was elected to Congress in 1897. He promoted legislation to remove Indians from reservations, believing assimilation would lead to equality.

(3) Wikipedia encyclopedia – Internet

(4) The New York Times, published April 9, 1872

(5)Newspaper Chronicle of the Indian Wars, Volume 4, compiled by Marc H Abrams, Published 2010, Page 16

(6) The New York Times, published September 1, 1874

(7) My life on the Plains by Custer, representing the major part of Custer’s life, was first published some two years before the General’s Death. It is a vivid picture of the American West, the rigors of life for the settlers, and the horrors of Indian warfare. The first edition of the book included a chapter by General W R Hazen which Hazen later privately published separately as a pamphlet entitled These Barren Lands.

(8)His articles on the Plains Indians were first published in the Galaxy Magazine 1872-74, and then incorporated into his book, My Life on the Plains, or, Personal Experiences with Indians, published in 1874.

(9) Robert Strahorn spent his life writing and promoting. Instrumental in settling west of the Missouri river and developing its resources. He was one of the best at selling something that existed only in dreams. He touted farmland Often land so tough it would take 3 generations to succeed.

(10) The New York Times, published April 28, 1874

(11) The New York Times, February 1, 1874