Members of the Seventh Cavalry Who Later Lived and/or Died in the LBH Region (Montana, Wyoming, North Dakota, South Dakota) Including the Indian Scouts but Excepting Those Who Died in Other Battles

Joseph Bates, a private in M Company who participated in the valley and hilltop fights, died on September 13, 1893, in Sturgis, South Dakota, and was buried there in St. Aloysius Cemetery.

Black Calf, an Indian scout also known as Boy Chief, was with Reno’s Column. He died on June 4, 1922, in Armstrong, North Dakota.

James P. Boyle, a private in G Company who participated in the valley and hilltop fights and was wounded in the back, died on September 2, 1920, in Bismarck, North Dakota. He was buried on September 14, 1920, in St. Mary’s Cemetery, in Bismarck (Lot 8, Row 8, Block A).

Carl August Bruns, a private in E Company who was on detached service at the time of the battle, died on January 4, 1910, in Mandan, North Dakota.

John W. Burkman, also known as Old Neutriment, committed suicide on November 6, 1925, in Billings, Montana.

Michael C. Caddle, a sergeant in I Company who was on detached service at the time of the battle, died on May 1, 1919, in Bismarck, North Dakota.

Charles A. Campbell, a Private with Company B who was with the pack train and in the hilltop fight, died on August 2, 1906, in Bismarck, North Dakota.

John C. Creighton, also known as Charles Chesterwood, resided at 107 Seventh Avenue, Mandan, North Dakota, in 1927.

William Cross, a scout, died in July 1894 in Culbertson, Montana.

Curly, an Indian scout, died on May 21, 1923, at the Crow Agency.

William A. Curtiss, a sergeant with F Company, died on October 27, 1888, in Helena, Montana Territory.

John F. Donohue died on December 3, 1924, in Butte, Montana.

Peter Eixenberger, one of the musicians who stayed aboard the Far West, died on September 12, 1917, in Sykes, Montana, and is buried at St. Aloysius Cemetery in Sturgis, South Dakota.

James Flanagan, a sergeant in D Company who was in the hilltop fight, died on April 21, 1921, in Mandan, North Dakota.

Moses E. Flint, a packer with the Quartermaster staff, was with the pack train and in the hilltop fight. He died in 1902, presumably in South Dakota, and was buried at Spring Valley Cemetery in Pollock, South Dakota.

Harvey A. Fox, who was not at the battle, died on March 28, 1913, in Warm Springs, Montana.

Peter Gannon, who was not at the battle, died on June 12, 1886, at Fort Assinniboine, Montana Territory, where he was originally buried. He was reinterred on March 27, 1905, at the Custer Battlefield National Cemetery, Montana, in Section B, Site 1285.

Edward Garlick, First Sergeant in G Company, was on furlough at the time of the battle. He died on January 25, 1931, in Sturgis, South Dakota.

Goes Ahead, an Indian scout, died on May 31, 1919, at the Crow Agency and is buried in Custer Battlefield National Cemetery.

Hairy Moccasin died on October 9, 1922, in Lodge Grass, Montana, and was buried on October 11, 1922, in Saint Ann’s Cemetery in Lodge Grass, Montana.

Half Yellow Face died in 1879 at Fort Custer, Montana Territory.

John E. Hammon, a corporal in G Company who participated in the valley and hilltop fights, died on January 19, 1909, in Sturgis, South Dakota. He was buried in Bear Butte Cemetery, in Sturgis, South Dakota.

George B. Herendeen died on June 17, 1918, in Harlem, Montana.

Max Hoehn, a private in L Company who was on detached service at the time of the battle, died on January 6, 1911, in Sturgis, South Dakota. He was buried at St. Aloysius Cemetery in Sturgis.

Jacob Horner, a private in K Company who was on detached service at the time of the battle, died on September 21, 1951, in Bismarck, North Dakota.

John J. Keller died on February 8, 1913, in Butte, Montana.

Ferdinand Klawitter, a private in B Company who was on detached service at the time of the battle, died on May 17, 1924, in Nax, North Dakota.

John Lattman, a private in G Company who participated in the valley and hilltop fights, died on October 7, 1913, in Rapid City, South Dakota. He was buried in Elk Vale Cemetery which is east of Piedmont, South Dakota.

Little Sioux, an Indian scout who was with Reno’s column in the valley fight, died on August 31, 1933, in North Dakota.

John J. Mahoney, a private in C Company who was with the pack train and in the hilltop fight, died on July 27, 1918, in Sturgis, South Dakota and was buried at St. Aloysius Cemetery in Sturgis.

Samuel J. McCormick, a private in G Company who was in the valley and hilltop fights, died on September 10, 1908, in Fort Meade, South Dakota. He was buried in Bear Butte Cemetery in Sturgis, South Dakota.

Thomas F. McLaughlin, a sergeant in H Company who was wounded in the hilltop fight, died on March 3, 1886, in Jamestown, North Dakota.

Jan Moller, who was also known as James Moller, was a private in H Company who was wounded in the hilltop fight. He died on February 23, 1928, in Deadwood, South Dakota, and was buried there in the Mount Moriah Cemetery.

Lansing A. Moore died on July 27, 1931, in Rawlins, Wyoming.

William O’Mann, a private in D Company who was in the hilltop fight, died on April 26, 1901, in Fargo, North Dakota.

Daniel Newell, a private in M Company who participated in the valley and hilltop fights and was wounded, died on September 23, 1933, in Hot Springs, South Dakota. He was buried in Bear Butte Cemetery in Sturgis, South Dakota.

John Pahl, a sergeant in H Company who was wounded in the hilltop fight, died on January 28, 1924, in Hot Springs, South Dakota and was buried in Bear Butte Cemetery in Sturgis, South Dakota.

James Pym died on November 29, 1893, in Miles City, Montana.

Michael Reagan, who was not at the battle, died in 1917, in Columbia Falls, Montana.

Red Bear, who was also known as Good Elk, was an Indian scout who was in the valley fight. He died on May 7, 1934, in Nishu, North Dakota.

William Sadler, a private in D Company who was on detached service at the time of the battle, died on November 12, 1921, in Bismarck, North Dakota.

Hiram Wallace Sager may have homesteaded in the Black Hills of South Dakota in 1887. See http://ftp.rootsweb.com/pub/usgenweb/sd/campbell/land/camp-st.txt.

James W. Severs died about 1912 in Rock Springs, Wyoming.

Walter Scott Sterland, a private in M Company who was on detached service at the time of the battle, died on August 27, 1922, in Bismarck, North Dakota.

Strikes the Bear, an Indian scout who crossed the river with Reno’s Column, died on June 7, 1929, in Ree, North Dakota.

Strikes Two, an Indian scout who crossed the river with Reno’s Column, died on September 8, 1922, in Elbowood, North Dakota.

Peter Thompson, a private in C Company who was wounded in the hilltop fight and later awarded the Medal of Honor, died on December 3, 1928, in Hot Springs, South Dakota. He was buried in the Masonic Section of the West Cemetery in Lead, South Dakota.

James Weeks died on August 26, 1877, on the Crow Agency in Montana Territory.

Henry Charles Weihe, who was also known as Charles White, was a sergeant in M Company who fought in the valley and hilltop fights and was wounded. He died on October 23, 1906, in Fort Meade, South Dakota, and was buried in the Old Post Cemetery at Fort Meade.

John S. Wells, a sergeant in E Company who was on detached service at the time of the battle, died on July 16, 1932, in Dickinson, North Dakota.

Adam Wetzel died on March 20, 1909, in Bozeman, Montana.

White Man Runs Him died on June 2, 1929, in Lodge Grass, Montana, and is buried at the Custer Battlefield National Cemetery on the Crow Agency, Montana.

White Swan died on August 12, 1904, on the Crow Agency, Montana.

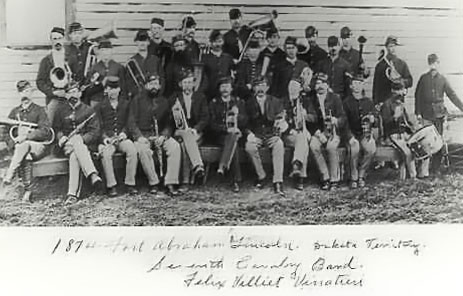

Felix Villiet Vinatiere, the Seventh Cavalry’s Chief Musician, was not present at the battle. He died on December 15, 1891, in Yankton, South Dakota.

Charles A. Windolph died on March 11, 1950, in Lead, South Dakota. He is buried in the Black Hills National Cemetery in Sturgis, South Dakota.

James Wynn, a private in D Company who was in the hilltop fight, died on March 21, 1892, in Fort Yates, North Dakota.

Younghawk, an Indian scout who participated in the valley and hilltop fights, died on January 16, 1915, in Elbowood, North Dakota.