Times and statements in bold are based on John S. Gray’s tables in Custer’s Last Campaign: Mitch Boyer and the Little Bighorn Reconstructed, compiled by Diane Merkel with comments (regular font) from members of the Little Bighorn History Alliance Message Boards with their sources in parentheses.

June 25, 1876

AM

12:30: The main column left the Busby camp on a night march under Custer.

2:50: 1st Lieutenant Charles Varnum and scouts arrived at a pocket below the Crow’s Nest.

3:15: The main column arrived at Halt 1 on Davis Creek where it was still dark. Local time = MST – 13 minutes to allow for sun transit at 12:13 at Busby and Crow Agency, MT. On a clear, moonless night, the first streaks of day appear at 1:55 local time. A pocket watch like Wallace’s can be read at 2:45 AM. It is daylight at 3:00 (Reno Court of Inquiry [hereinafter RCOI]: Wallace, Moylan, Benteen). Visibility is clear to the horizon by 3:18 although you cannot read print until 3:30. (All based on personal observation from the divide.) Wallace’s Official Report stated the night march ended about 2:00 (Federal View, p. 65). Godfrey (diary, p. 10) stated they halted the night march about 2 o’clock. Herendeen (RCOI) stated they marched until probably 2:00. Peter Thompson (Magnusson, p. 95) stated, “As soon as the first faint streaks of daylight appeared, we moved into a grove where we were ordered to unsaddle and rest for several hours.”

3:40: Two Crows saw the Sioux village at the Little Bighorn for the first time. From accounts by Red Star and Little Sioux, this could have been as early as just after 3 AM. It would be easily visible by 3:00 local time (personal observation).

3:50: Varnum was awakened for the climb to the peak. This would have been no later than 3:15 since Varnum (Northwestern Fights and Fighters, p. 340) said he got to the Crow’s Nest about 2:30, slept 45 minutes, and was awakened when it was just daylight, probably closer to 3:00 AM.

4:00: Varnum and the scouts study the village in the Little Bighorn Valley.

5:00: Varnum and the scouts saw the breakfast smoke at the Halt 1 camp.

5:20: Varnum sent two Ree scouts with a note to Custer who was still at Halt 1. It was possible for Varnum to have sent the messengers significantly earlier; e.g., 4.30 AM. Varnum (Northwestern Fights and Fighters) said 4:45 or 5:00. Translated to local time, that is closer to 3:30, more likely since Girard and the Ree scouts said Custer got Varnum’s message at 4:00 or when the sun was just rising, 4:09 local time. Note that Gray’s use of “Halt 1” can be/is somewhat confusing since Wallace uses “Halt 1” to refer to the halt at the divide and “Halt 2” to identify the halt over the divide when Benteen was sent to the left. I now think it possible Varnum was using HQ time so he sent the messenger at 3.40 AM. This fits with the messenger arriving as reported by the Rees as the sun was rising; i.e., 4.13 AM.

5:40: The Crows saw two Sioux west of the Divide.

6:20: Varnum led a sortie against the two Sioux.

6:40: Varnum returns to the Crow’s Nest, unsuccessful.

7:10: The scouts saw two Sioux crossing the divide.

7:20: The two Ree couriers arrived at the Halt 1 camp from the Crow’s Nest. The assumption that the main courier travelled so slowly (less than 3 mph) is very doubtful and the journey time could easily be half the two hours claimed here. Cf. note above: Girard and Rees put it at 4:00-4:09 (Girard, Once Their Home, p 263; Arikara Narrative, p 149).

7:30: Custer read Varnum’s note, indicating that a village had been spotted in the Little Bighorn Valley.

7:45: Sergeant Curtis left the Halt 1 camp on the back trail in search of a lost pack.

8:00: Custer’s Crow’s Nest party (Fred Girard, Bloody Knife, Red Star, Little Brave, and Bob Tailed Bull) left Halt 1 for the Crow’s Nest. If the above comments are correct, Custer could have departed at least one and possibly two hours earlier. I now think Custer rode round the camp before 5am to tell troop commanders that the column would not march at the standard 5 AM but to be ready by 8 AM. This would have been the time Custer expected to return from the Crow’s Nest. Custer departed at or soon after 5 AM for the Crow’s Nest and arrived there as reported by White Man Runs Him at 6 AM (Custer Myth, p 15). Varnum recalled that Custer arrived from the coffee camp with the column, not before it. Herendeen and Churchill made the departure from the early halt at 7:00 or 7:30 (RCOI). Donohue (Fatal Day, p. 20) thought the column left at 6:00. Remembered times are always earlier than Wallace’s official time. Edgerly (“Narrative,” Research Review, 1986, p 5) says George Custer went up to the Crow’s Nest about 9 AM, “when the column halted, the command having previously halted from 2 to 5, without unsaddling” (Herendeen in Custer Myth, p 262) “About nine o’clock on the morning of the 25th of June and the last day of our march Custer halted his troops and concealed them as well as he could. . . .[Then he went to the Crow’s Nest.] Custer was gone perhaps an hour or an hour and a half. . . .”

8:05: Custer’s party was spotted by two Sioux as seen from the Crow’s Nest. Varnum saw two Sioux meeting Custer’s party.

8:25: Curtis party sights Cheyennes rifling through the lost pack.

8:45: Command under Reno departed Halt 1 camp and moved toward the Crow’s Nest. I now think the column marched at 7.25 AM under Tom Custer and met the irate Custer on his return from the Crow’s Nest as he had ordered the column to stay put. (See various Girard accounts.)

9:00: Custer’s party arrived at the Crow’s Nest.

9:00+: Custer studied the valley and discussed the findings.

10:07: Custer and the scouts watched the command arrive at the Halt 2 camp on Davis Creek for concealment.

10:20: Custer’s party left the Crow’s Nest with Varnum’s party. Curtis’ party arrived at the Halt 2 camp and reported seeing the Cheyennes with the lost pack.

10:30: Custer and the scouts are met by Captain Thomas Custer with Sergeant Curtis’ news.

10:35: Custer-Varnum party arrived at the Halt 2 camp. Cheyennes were spying. There is some evidence (De Rudio, Hare via Camp) that Custer made a second visit to the Crow’s Nest. The time taken for this would not be more than 30 minutes if Halt 2 was near the Crow’s Nest.

10:50: At officer’s call, Custer decided they will attack. Benteen (RCOI) and Edgerly (Custer Myth, pp 216, 219) put officers’ call at 10:00, after Custer had been on the Crow’s Nest for about an hour (Research Review, 1986; see also Donohue in Fatal Day, pp 20-21). Herendeen very early, therefore very reliably, put it between 10:00-10:30 (Custer Myth, p. 280).

11:45: Command under Custer departed Halt 2 camp and moved down Davis Creek. This departure time assumes the command halted within 0.75 mile of the Divide. It is likely that they were actually at least twice as far as this since participants reported the column as being concealed in a ravine. This would pull forward the departure time by 15 minutes or so. Hare, DeRudio, and Varnum agreed that the column was halted 1/4 to 1/2 mile east of the divide.

PM

Noon: Command passed the Crow’s Nest and crossed the Divide. There is substantial testimony that the time for this event was significantly earlier. From comments above, it is not impossible that it was.

12:05: Command at Halt 3; Custer assigned the battalions. This is Wallace’s Halt 2, about 1/2 mile west of the divide. McDougall stated (RCOI): “On June 25th, about 11 o’clock a.m., I reported to General Custer for orders. He told me to take charge of the pack train and act as rear guard.” If Wallace’s watch (itinerary) was set to HQ St. Paul time — and Godfrey said definitely, “Our watches were not changed,” (RCOI) — Wallace’s 12:05 is approximately equal to 10:45 local time, within 15 minutes of McDougall’s recalled 11:00. cf. Friedman recalled time is accurate within one hour excluding the possibility of chance (Memory & Cognition 15.6, 1987, pp 518-20).

12:12: Custer-Reno battalions left the divide half to descend to Reno Creek. Benteen’s battalion left the divide halt on an off-trail scout to the left. It is unlikely that all three columns actually set off at precisely the same time, but the impact is only a few minutes.

12:32: The packtrain left the divide half on Custer’s trail.

1:20: Benteen’s battalion arrived at upper No-Name Creek and turned down it. On a high ridge ahead, 1st Lieutenant Francis Gibson found the Little Bighorn valley empty. Many years later. Lt Gibson expressed doubt that he had actually viewed the correct valley (see interview with Camp).

2:00: Custer-Reno battalions passed No-Name Creek. Reno was called to the right bank. Knipe and Ryan, as well as Reno, say Reno was called to the right bank near the Lone Tepee. This subtracts a mile from Gray’s itinerary.

2:15: Custer-Reno battalions passed the lone tepee. Custer’s battalion left down the right bank of Reno Creek. The scouts reported Sioux in the Little Bighorn Valley. Custer ordered Reno to lead out at a trot.

2:17: Boston Custer trots ahead of the packtrain to overtake Custer.

2:32: Benteen’s battalion arrived at Reno Creek, 1/4 mile above the mouth of No-Name Creek. They saw the packtrain 3/4 mile above. Boston Custer joins them. Benteen (Custer Myth, p 180) recalled being at the morass at 1:00 PM. Godfrey thought 2:00. Assuming Hutchins/Knipe are right about the location of the morass, it is near the mouth of the South Fork.

2:37: Benteen’s battalion reached the morass to water the horses. Boston Custer trotted on.

2:43: Custer’s battalion trotted to the flat right behind Reno. The scouts reported the Sioux were alarming the village. Reno was ordered to charge taking Adjutant William W. Cooke. Custer sent two scouts to the bluff who joined Reno.

2:45: Boston Custer passed the lone tepee.

2:47: At the North Fork, Reno’s battalion crossed to the left bank of Reno Creek.

2:51: Custer’s battalion made a fast walk to the North Fork and halted to water.

2:53: Reno’s battalion crossed to the left bank of the Little Bighorn River at Ford A where it halted to water the horses and reform. The troops and the scouts saw the Sioux attacking.

2:55: Cooke left to report to Custer.

2:57: Benteen’s battalion departed the morass as the packtrain arrived. The packtrain halted to water and close up.

3:01: Cooke reported the Sioux were attacking Reno. Custer’s battalion started down the right bank of the Little Bighorn River, leaving the north fork of Reno Creek.

3:03: Reno’s battalion left Ford A and started its charge down the left bank of the Little Bighorn River. If Reno crossed Reno Creek near the Lone Tepee at 2:00 according to Wallace’s watch, he was about 3-3.5 miles from Ford A. The column proceeded at a trot or “slow gallop” for 15 minutes, again according to Wallace. This would cover about 2 miles at 7.5-8 mph. Wallace said Reno was ordered to attack about 2:15. He took the gallop and covered the remaining mile to the river in about 5 minutes (gallop 9-11 mph in Upton, 1 mile in 6 minutes according to Cooke) and crossed at Ford A at 2:20 in Wallace’s recollection. Using Anders’/ Graham’s 1 hour 20 minute difference between local time and official HQ time, then Reno crossed Ford A near 1:00, consistent with recollections of Girard, Porter, Knipe, and Taylor. Gray added 43 minutes and at least two miles between Reno’s crossing of the creek and fording the Little Big Horn.

3:05: Reno’s battalion saw Custer or the scouts on the right bank bluff.

3:10: Pony captors leave the Reno charge to capture Sioux herd. Hare (Custer in ’76, p. 65) said he and the Rees rode down the valley while Reno was watering the horses (i.e., crossing river?) and the Rees took off from him about a mile down river. William Jackson (William Jackson, His True Story, p.135) said scouts rode out ahead of Reno and turned straight down valley.

3:12: Benteen’s battalion walked past the lone tepee.

3:13: Reno’s battalion saw Custer’s battalion at Reno Hill. Custer’s battalion saw Reno charge and the village.

3:15: Sgt. Daniel Kanipe left for Capt. Frederick Benteen and the packtrain.

3:17: The packtrain left the morass.

3:18: Reno’s battalion halted and formed a skirmish line. They saw Custer’s battalion on the bluffs, disappearing. Custer’s battalion passed Sharpshooter Ridge and entered Cedar Coulee. Reno’s attack/formation of the skirmish line occurred about midday, probably 1:00 PM.

3:20: Little Sioux (Ree), Strikes Two (Ree), Red Star (Ree), Boy Chief (Ree), One Feather (Ree), Bull Stands in Water (Ree), and Whole Buffalo (Sioux) diverged from Reno’s charge and drove captured Sioux ponies up the bluff. They were joined there by seven stragglers who lagged behind on Custer’s trail and never crossed the Little Bighorn: Soldier (Ree), Stabbed (Ree), Bull (Ree), White Eagle (Ree), Red Wolf (Ree), Strikes the Lodge (Ree), and Charging Bull (Ree). If they left the column at 3:10 (above), how could they diverge from Reno’s charge at 3:20?

3:23: Custer’s battalion arrived at the bend of Cedar Coulee and halted.

3:24: Custer, his officers, Mitch Boyer, and Curley left the bend on a sidetrip to Weir Peak.

3:26: Three Crows left the halted command at the bend of Cedar Coulee (off-trail). Goes Ahead Tepee Book (2.6 June 1916) p.604 says scouts were told to make their escape at the trenches of the Reno-Benteen site.

3:28: Custer’s party arrived at Weir Peak and saw the village and Reno skirmishing.

3:28.5: The three Crows halted on the bluff above Weir Peak.

3:30: DeRudio saw Custer’s party at Weir Point. Custer’s party saw the concealed route to Ford B and the village. Not possible to identify individual and/or clothing on Weir from valley position. Who DeRedio saw remains open to question.

3:31: Custer and officers left Weir Peak to return to the command. The Arikara were fired on by the last of Custer’s column as it was disappearing over Weir (on the eastern edge), crossed Kanipe’s route, and encountered stragglers left behind Custer’s column (Custer in ’76, pp 180-1; Arikara Narrative, pp 115-6).

3:32: The packtrain passed the lone tepee.

3:32.5: Boston Custer passed Reno Hill. The Reno fight would have been visible for the next five minutes.

3:33: Reno withdrew the battalion into the timber. The three Crows saw Reno’s skirmish, fired at the Sioux, and left.

3:34: Custer returned to the halt at the bend from Weir Peak. Trumpeter John Martin left Custer’s battalion at the bend of Cedar Coulee for Benteen. Custer started down Cedar Coulee.

3:36: Pony captors overtook and passed Sergeant Kanipe.

3:38: John Martin met Boston Custer at the head of Cedar Coulee.

3:39: The three Crows halted, had a drink in the Little Bighorn River, and captured five ponies.

3:40: John Martin saw Reno’s battalion fighting in the timber.

3:40:5: Benteen’s battalion met the Rees driving the Sioux ponies.

3:42: Sergeant Daniel Kanipe meets Benteen’s battalion with a verbal message from Custer.

3:45: Little Sioux (Ree), Strikes Two (Ree), Red Star (Ree), Boy Chief (Ree), One Feather (Ree), Bull Stands in Water (Ree), Whole Buffalo (Sioux), Soldier (Ree), Stabbed (Ree), Bull (Ree), White Eagle (Ree), Red Wolf (Ree), Strikes the Lodge (Ree), and Charging Bull (Ree) drove the herd of Sioux ponies back to the packtrain and halted. Pretty Face (Ree) was with the packs until this time.

3:46.5: Custer’s battalion halted at the mouth of Cedar Coulee.

3:48: The packtrain met Kanipe who had Custer’s message.

3:49: Boston Custer overtakes Custer’s battalion at the mouth of Cedar Coulee with news. The three Crows continued upriver.

3:52: Black Fox (Ree) was at the bluffs and joined the three Crows who were given a Sioux pony.

3:53: Reno ‘s battalion began its retreat upstream. Girard (RCOI) puts this about 2:00. His watch, giving the time of sunrise near 4:00 AM local time and full dark at 9:00 PM, reflects local time fairly closely. Additionally, Girard’s watch times closely match the captured Rosebud watch, timing the entire fight from skirmish line to the surround on Reno Hill from 1:00-4:00. It is, per Hardorff, extremely unlikely that Crook, who was headquartered in Omaha, should have set his command watches to San Francisco time. HQ is where the general is, and the general had been in the field (Douglas, Wyoming, approximates HQ) for more than a year. HQ time is what the general says it is. Why set watches an hour and a half off daybreak or noon?

3:55: Rees switched to fresh Sioux ponies and started back to Reno. Custer’s battalion saw signals by Mitch Boyer and Curley on Weir Ridge.

3:56.5: Custer’s battalion started down Medicine Tail Coulee.

3:58: Benteen’s battalion met Trumpeter John Martin at the flat where they heard firing. The three Crows passed Reno Hill and saw Reno’s retreat.

4:00: Reno’s battalion retreats across the Little Bighorn River. Bob-tail Bull (Ree) and Little Brave (Ree) had been killed on the east bank by this time.

4:02: Benteen’s battalion took Custer’s trail at the North Fork.

4:04: Custer’s battalion halted in Medicine Tail Coulee where Boyer and Curley joined them.

4:04:5: The packtrain was overtaken by the Rees who were returning to Reno Hill.

4:05: Young Hawk’s party was trapped on the east bank bottom by the Sioux and fought. Herendeen’s party scrambled back to the timber from the retreat.

4:06: Benteen’s battalion saw Reno’s retreat at the knoll and halted.

4:08: Yates’ battalion (Companies F and E, off-trail) left the separation halt down Medicine Tail Coulee. Custer’s battalion (Companies C, I, and L) left the separation halt north out of Medicine Tail Coulee.

4:10: Benteen’s battalion met three Crows and one Ree and left the halt. Reno’s battalion climbed the bluffs obliquely to Reno Hill. William Baker (1/2 Ree), William Cross (Ree, 1/2 Sioux), Red Bear (Ree horse herder), White Cloud (Sioux rear guard), Ma-tok-sha (Sioux), and Caroo (Sioux) arrived at Reno Hill. Red Bear and White cloud left to join the pony captors. Herendeen’s party met 12 troopers who had been left in the timber.

4:15: Red Bear and White Cloud met three Crows and Black Fox and halted to await the return of the Crows.

4:16: Custer’s battalion arrived on Luce Ridge and halted on the defensive position.

4:18: Yates’ battalion arrived at Ford B. Light firing over the Little Bighorn began. Custer’s battalion saw and heard the firing.

4:20: Benteen’s battalion reached Reno Hill and joined Reno’s battalion. Three Crows and Black Fox arrived. The three Crows left to go downstream, passing Reno Hill, to find Reno’s two Crows. Custer’s battalion saw the Sioux coming up Medicine Tail Coulee to attack. I think the Gray time of 4:20 for Benteen on Reno Hill is completely wrong, and the time to be used is either 2:30 PM as per the Official Army Report or 3:45 PM which was Wallace’s HQ time estimate based on his testimony at RCOI, which he miscalculated as being 4:00 PM. Gray’s understanding of the time of events by this stage is so wrong that it is not really possible to comment further. There is no primary source evidence to support Gray’s 4:20 PM for this meeting.

4:23: Yates’ battalion crossed Deep Coulee and arrived on the cutbank unopposed. Custer’s battalion saw Yates start up the west rim of Deep Coulee.

4:25: Red Bear and White Cloud left for Reno Hill when the Crows failed to return. Custer’s battalion pinned down the Sioux with heaving firing.

Young Hawk’s party and Herendeen’s party heard heavy Custer firing downstream. Reno left in search of Hodgson’s body.

4:27: The packtrain halted at the flat to close up. Mathey sighted smoke. Custer’s battalion left Luce Ridge to meet Yates downstream.

4:30: Black Fox arrived at Reno Hill. Red Bear and White Cloud arrived for the second time. Young Hawk’s party and Herendeen’s party saw the Sioux leave the upper valley. The three Crows arrived at Sharpshooter Hill and heard Custer’s battalion firing.

4:32: Little Sioux, Strikes Two, Red Star, Boy Chief, One Feather, Bull Stands in Water, Whole Buffalo, Soldier, Stabbed, Bull, White Eagle, Red Wolf, Strikes the Lodge, Charging Bull, and Pretty Face returned to Reno Hill with the ponies from the lone tepee and were greeted by Red Bear and White Cloud. Custer’s battalion arrived at Nye-Cartwright Ridge.

4:33: Yates’ battalion ascended the west rim of Deep Coulee. The Sioux attacked its flanks.

4:38: Custer’s battalion fired at the Sioux on their left flank while negotiating a crossing of upper Deep Coulee.

4:40: Three Crows arrived at Reno Hill, reporting to Red Star that two Crows were killed.

4:45: Young Hawk’s party left for Reno Hill. Three Crows left for their home village.

4:46: Yates’ battalion fought on foot to the reunion point. Custer’s battalion joined Yates.

4:47: The packtrain left the flat and saw the troops on Reno Hill.

4:50: Reno returned from his search for Hodgson and talked with Varnum. Curley left Custer’s battalion for the mouth of the Bighorn.

4:52: Reno dispatches 2nd Lieutenant Luther Hare to speed up the ammunition mules.

4:55: The sound of Custer’s volleys prompted Capt. Thomas B. Weir to ask to move downstream.

4:57: The packtrain was at the North Fork and took Custer’s trail.

5:00: Young Hawk (Ree), Forked Horn (Ree), Red Foolish Bear (Ree), and Half Yellow Face (Crow) arrived at Reno Hill after being trapped on the east bank. White Swan (Crow) and Goose (Ree) who had been wounded and trapped on the east bank arrived on Reno Hill. They met Varnum and Reno.

5:02: The packtrain met Lieutenant Hare who had orders for the ammunition packs. Reno ordered Varnum to bury Hodgson, but they were awaiting tools.

5:05: Weir and Company D departed Reno Hill in search of Custer.

5:10: Herendeen’s party noticed that the heavy firing diminished, and they left with 12 troopers.

5:10-12: Custer’s last heavy firing was heard on Reno Hill.

5:12: 2nd Lieutenant Hare arrived on Reno Hill in advance of the ammunition mules.

5:15: Reno dispatched 2nd Lieutenant Hare to the north after Weir with orders to contact Custer.

5:19: Two ammunition mules arrived with tools.

5:21: Varnum left to bury Hodgson.

5:22.5: Benteen departed Reno Hill with Companies H, K, and M to join Weir.

5:25: McDougall, Company B, and Mathey arrived with the packtrain. Weir’s Company D arrived at Weir Ridge and halted. Both Companies B and D saw that the Custer fight has ended.

5:29: Herendeen’s party met Varnum’s burial party.

5:30: The Ree horse herders left Reno Hill for the Powder River. The Ree rear guard left to join the Weir advance party.

5:32: Herendeen’s party met the Ree rear guard on the Weir advance.

5:32.5: Hare left Weir Ridge to report to Reno.

5:35: George B. Herendeen, who had been left in the timber, arrived at Reno Hill. Benteen and Companies H, K, and M arrived at Weir Ridge and halted. All saw the Sioux coming to attack.

5:35+: Herendeen interpreted for Half Yellow Face and Reno.

5:40: Reno and his orderly left to join the Weir advance.

5:42.5: Benteen and Company H left Weir Ridge to find Reno. Hare met and joined the Reno party.

5:43: Varnum returned from his burial mission and joined Company A.

5:47.5: Benteen and Company H met the Reno party and halted for 10 minutes during which time they conferred. Hare left the halt for van with Reno’s retreat order. The impedimenta left Reno Hill for the Weir advance.

5:50: Hare arrived at Weir Ridge and joined Company K. Companies D, K, and M left Weir Ridge for Reno Hill.

5:52.5: Companies A, B, G, and the packtrain left to join the Weir advance. Reno, Benteen, and Company H left the halt for Reno Hill.

5:55: The rear guard, chased by the Sioux, passed Reno Hill while heading for the Powder River.

5:57.5: Reno, Benteen, and Company H met the impedimenta and ordered it back.

6:00: Reno, Benteen, and Company H arrived at Reno Hill.

6:02.5: Companies D, M, A, B, G and the packtrain arrived at Reno Hill.

6:10: Godfrey, Hare, and Company K, covering the retreat, arrived at Reno Hill and covered the rear.

6:17: The horse herders passed the lone tepee and slowed down.

6:43: The rear guard passed the lone tepee and slowed down.

7:47: The horse herders saw that the “sun touches hills.”

8:13: The rear guard was six miles beyond the lone tepee.

8:30?: The horse herders heard shots ahead and a pursuit behind them. They lost the trail. The rear guard experienced the final attack by the pursuing Sioux.

8:47: The rear guard passed the divide “before dark.”

9:00: The evening battle at Reno Hill ended at dark.

9:17: The horse herders halted to water, then crossed the divide “in dark.”

11:45: The rear guard passed the Rosebud (Busby).

June 26

AM

12:04: The horse herders passed Rosebud (Busby) “at midnight.”

4:00: The rear guard passed Lame Deer Creek “at daylight.”

4:19: The horse herders arrived at Lame Deer Creek “at daylight” and camped.

PM

5:15: The rear guard arrived at the mouth of the Rosebud “in evening” and camped.

8:00: The horse herders left their camp “at sundown.”

Time? Fred F. Gerard and William Jackson (Ree, 1/4 Blackfoot), who had been left in the timber, arrived at Reno Hill.

JUNE 27

AM

8:00: Black Fox overtook the rear guard at “8 A.M. breakfast.”

11:35: The horse herders arrived at the mouth of the Rosebud.

PM

5:30: The rear guard camped for the night at the Tongue River.

7:05: The horse herders camped for the night just short of the Tongue River.

JUNE 28

AM

PM

2:00: The rear guard arrived at the Powder River base camp

7:00: The horse herders arrived at the Powder River base camp.

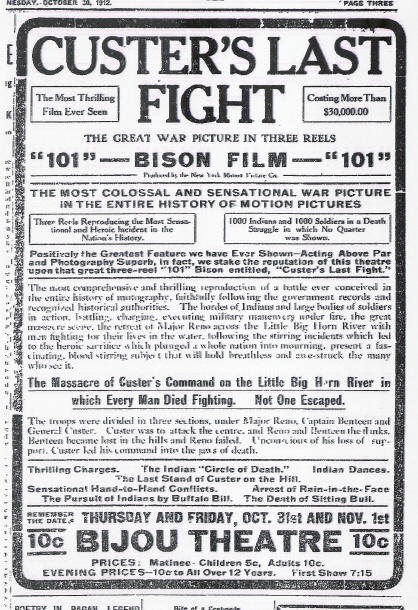

© Denver Public Library, Western History Collection.

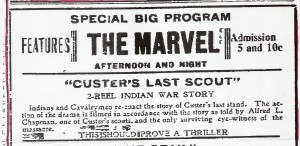

© Denver Public Library, Western History Collection.